However, this treatment is complicated by adverse immune reactions of the donor cells, a slow immune reconstitution, and a lack of suitable donors for most patients. Replacing the affected bone marrow with allogeneic healthy (stem) cells is currently the only established therapy for SCID. As a consequence, RAG-SCID patients lack B and T cells and develop many serious, life-threatening infections, especially pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis, as neonates. These patients have mutations in RAG1 or RAG2, which are required for the assembly of the T-cell receptor and B-cell receptor ( 4, 5, 6). The second or third most common form of SCID (depending on the genetic background of the population) is RAG-negative SCID. Mutations in the ADA gene allow the buildup of deoxyadenosine to levels that are toxic to lymphocytes, in particular immature thymocytes. ADA converts deoxyadenosine into nontoxic deoxyinosine. The ADA enzyme is found throughout the body but is most active in lymphocytes. ADA-SCID patients fail to make T cells, B cells, and NK cells, experience recurrent infections, and fail to thrive ( 3). For many types of SCID, the underlying molecular defect is unknown. Other forms of SCID are those with underlying deficiencies in the adenosine deaminase ( ADA) gene, recombinase-activating genes ( RAG), Artemis, or more rarely in the CD3 genes, ZAP70 and IL7R ( Figure 1). Although B cells are present, their function is severely impaired, not only because of a lack of T-cell help but also because of intrinsic B-cell defects. The incidence is estimated to be roughly 1 in 65,000 live births ( 2) The lymphocytes of patients with X-linked SCID cannot respond to the several essential cytokines (interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21) needed for these cells to develop, survive, and fight infections. Worldwide, the most common form of SCID is X-linked SCID, caused by mutations in the gene coding for the Il2Rγ chain, resulting in SCID with a T −B +NK − phenotype, referring to the lack of T lymphocytes and NK cells, but the presence of B lymphocytes in these patients. The diagnosis is established by detecting lymphopenia, absence or very low numbers of T lymphocytes, and impaired T-cell proliferative responses to mitogens.Ī number of genetic abnormalities can cause SCID. Most infants develop opportunistic infections within the first 6 mo of life. Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) is a heterogeneous disease characterized by lack of T lymphocytes and sometimes also B and/or natural killer (NK) cells ( 1). The Ig is obtained through human plasma donors.Immunodeficiencies invariably refer to defects in the immune system that lead to an increased risk of infections.

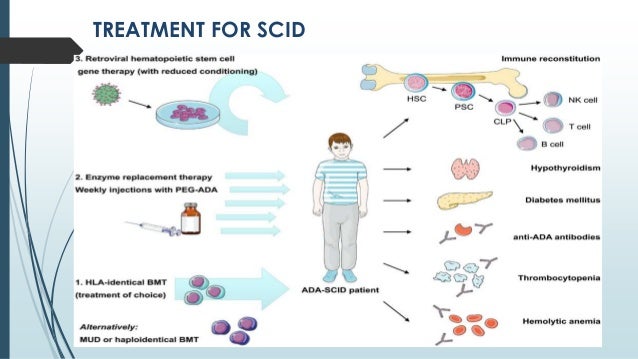

The child will also receive immunoglobulin therapy, or Ig, an infusion of antibodies designed to boost the child’s immune system. Prior to these treatments, a child with SCID will begin the treatment process by taking antibiotics, antivirals and antifungals to ward off infection. Eventually a person with ADA-SCID will require either HSCT or gene therapy for long-term results. The results are temporary and do not permanently repair the immune system. In enzyme replacement therapy, the missing enzyme is regularly injected into the person with SCID to boost the ADA enzyme. The repaired cells provide the child with a working immune system.Ī third treatment, enzyme replacement therapy, can be used for children and adults with ADA-SCID. In gene therapy, doctors extract a child’s defective blood-forming cells, correct the defect, and put the corrected cells back into the child. The donor cells provide the child with an immune system.Īnother less common but promising treatment option is gene therapy, which is currently in clinical trials.

In HSCT, doctors take healthy blood-forming cells that can develop into a healthy immune system from a donor and put them into a child. Most infants with SCID are treated with HSCT, or bone marrow transplant, which results in a new immune system that is able to fight infection. The best course of treatment for a child with SCID depends on several factors including the type of SCID, the child’s health, and doctor recommendations. If a child is diagnosed and treated within the first few months of life before the child has a serious infection, then the long-term survival rate is more than 90%. With early treatment, most children with SCID should be able to develop their own working immune system.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)